-

Charles Dickens and the Naming of Novels. From The Pickwick Papers to David Copperfield.

What’s in a name? that which we call a rose

William Shakespeare – Romeo and Juliet

By any other name would smell as sweet;Most of the novels and novellas of Dickens are generally known by their short titles. More often than not with the novels this is simply the name of the central character – a feature which is not particularly revealing about the sort of story one may expect between the covers. Most of them, however, have more expanded titles, or sub-titles, or expanded descriptions (in a few cases rather humorous in themselves.)

For ease of reference and convenience these short titles have become the norm – and appearing so simple they often mask the thought and process which went into the genesis of the name and the content/plan for the work they refer to. In the character limited world of Twitter and the like, even shorter versions serve to refer to the works. Trying to squeeze in a particularly juicy quote on Twitter I have often been reduced to the expedient necessity of initials, and thus the novels may be represented from first to last:

PP, OT, NN, OCS, BR, MC, D&S, DC, BH, HT, LD, ToTC, GE, OMF, ED

Long titles are unwieldy and take a good deal of utterance to say. I remember at Drama School taking great pains to learn the name of a play that we were studying in the first year. The play, by German playwright Peter Weiss, was called:

The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade

Is it any wonder that it is usually referred to as Marat/Sade

As seems to be the way with most of my posts thus far, this post will loosely contain discoveries I have made about the work that went into the selection of names and creation of the titles of the works. I doubt it will be fully comprehensive, but I hope it will contain interest enough.

To jump straight to the purport of the post and avoid my waffle (I feel a meandering coming on) you can do so by clicking here

I might have a misgiving that I am ‘meandering’ in stopping to say this…

David Copperfield – Chapter 2The Dickens Club, or to give it its full title (in keeping with the subject matter of this post) The Dickens Chronological Reading Club 2022 -2023, has reached David Copperfield*: the eighth full-length novel of the inimitable Charles Dickens.

[* I originally started this post when this statement was true (back in early April) we have now progressed to Bleak House and are in the final quarter of the novel. This fact does not substantially alter the content of the post, but may introduce a few ‘course correcting’ notes to crop up updating the ‘what was true then’ to ‘how the case stands now’]

Having discovered this wonderful community somewhere between novels 5 and 6, and not having previously read novels 1, 4, 5 or 6, I have been largely trying to catch up by reading with greedy eyes (and sometimes ears) such novels as will plug the gaps in my sequence. With novel 7 at the start of this year and four of five ‘Christmas Books’ preceding it, there was always going to be a dickens of a lot of Dickens between then and now!

Having briefly patted myself on the back for having produced audiobook versions of all five “Christmas Books” and of novels 2 and 3, I set to work in earnest.

Starting at the beginning of November last year, my approximate order of reading (in defiance of chronology) has been thus:

Martin Chuzzlewit, The Pickwick Papers, The Old Curiosity Shop, Dombey and Son, Barnaby Rudge.

Or to summarize in numeric form: 6, 1, 4, 7, 5 (Which as it happens is spookily close to my childhood telephone number – 2 of the digits being out by 1)

I don’t know what it is about Dickens’ writing that fills me with an overwhelming desire to instantly enter into audiobook production of the latest novel I have read by him, but it is invariably true. Since January I have been recording The Pickwick Papers alongside my other reading. I currently have 8 chapters remaining, and up to this point have had to voice some 223 distinct characters.** (And there I was thinking that Nicholas Nickleby was not to be surpassed in cast size (143 or thereabouts!)) I have a lurking suspicion that once I have finished Pickwick I am very likely to soon afterwards pay an audiobook visit to The Old Curiosity Shop! We shall see…

[**I have now finished the recording of Pickwick. The final count is 234 unique speaking characters —183M & 51F. The Old Curiosity Shop may still be the next of the novels I tackle, but I have now added to my list a desire to record Bleak House too!]

The following image goes some way to prove the veracity of the above paragraph 😀

Having finished Barnaby Rudge about a week before the Dickens Club embarked on David Copperfield, I thought I would prepare the way for ‘the most autobiographical’ of novels by working my way through John Forster’s The Life of Charles Dickens, at least as far as the Copperfield era. In addition to this, and concurrently I started listening to the audiobook version of Claire Tomalin’s biography, Charles Dickens: A Life.

I have managed to get far enough through the audiobook to tick that box, but Forster’s biography is rather huge and so wonderfully detailed that I have only managed to get as far as 1844.*** So, being some 4 years short and with so much detail before getting to even a contemplation of David Copperfield, I cheated and jumped ahead!

So many worlds, so much to do,

Tennyson

So little done, such things to be.These two biographies have me in their thrall and I shall continue to work through both and the delights therein contained. (Hopefully I shall have got far enough through Forster to be in the right year once we start the Bleak House read*** – this being another of the Novels I have yet to read, along with Little Dorrit, Our Mutual Friend and Edwin Drood)

[***I have read all of the Forster biography to the right point to synchronize my reading of the rest with the Dickens Club continuation through the novels]

So, after that interlude as to how I arrived at this point I feel quite ready to proceed with the post proper. As it was David Copperfield that led me into this rabbit-hole, I shall start therebefore heading back to The Pickwick Papers.

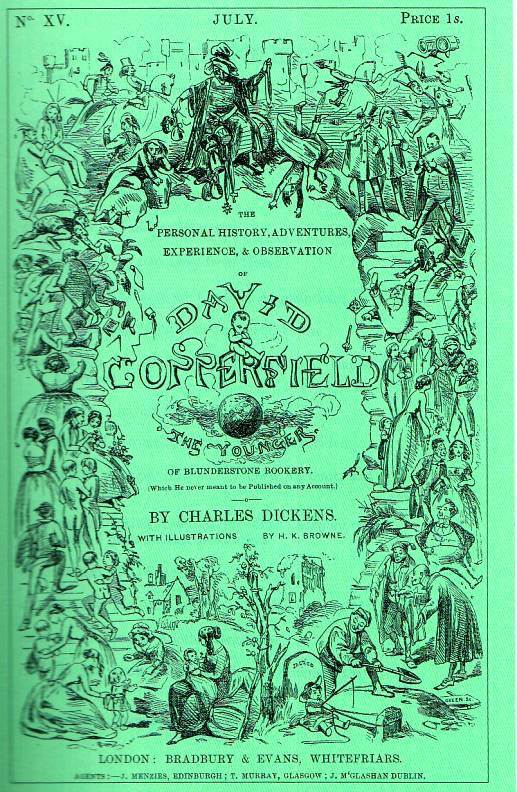

David Copperfield

Image source and further reading: Victorian Web The central illustration by Phiz on the monthly wrapper of the baby and the globe reflects the fact that this novel was very nearly called:

The Copperfield Survey of the World as it Rolled

The following slightly reduced excerpt from John Forster’s The Life of Charles Dickens details the almost 2 month process of title selection for what was to become Dickens’ ‘favourite child’

“Deepest despondency, as usual, in commencing, besets me;” is the opening of the letter in which he speaks of what of course was always one of his first anxieties, the selection of a name. In this particular instance he had been undergoing doubts and misgivings to more than the usual degree. It was not until the 23rd of February [1849] he got to anything like the shape of a feasible title. “I should like to know how the enclosed (one of those I have been thinking of) strikes you, on a first acquaintance with it. It is odd, I think, and new; but it may have A’s difficulty of being ‘too comic, my boy.’

Mag’s Diversions.

Being the personal history of

Mr. Thomas Mag the Younger,

Of Blunderstone House.This was hardly satisfactory, I thought; and it soon became apparent that he thought so too, although within the next three days I had it in three other forms.

1. Mag’s Diversions. Being the Personal History, Adventures, Experience and Observation of Mr. David Mag the Younger, of Blunderstone House.

2. Mag’s Diversions. Being the Personal History, Experience and Observation of Mr. David Mag the Younger, of Copperfield House.

The third made nearer approach to what the destinies were leading him to, and transformed Mr. David Mag into Mr. David Copperfield the Younger and his great-aunt Margaret; retaining still as his leading title, Mag’s Diversions.

It is singular that it should never have occurred to him, while the name was thus strangely as by accident bringing itself together, that the initials were but his own reversed; but he was much startled when I pointed this out, and protested it was just in keeping with the fates and chances which were always befalling him. “Why else,” he said, “should I so obstinately have kept to that name when once it turned up?”

It was quite true that he did so, as I had curious proof following close upon the heels of that third proposal. “I wish,” he wrote on the 26th of February, “you would look over carefully the titles now enclosed, and tell me to which you most incline. You will see that they give up Mag altogether, and refer exclusively to one name—that which I last sent you. I doubt whether I could, on the whole, get a better name.

1. The Copperfield Disclosures. Being the personal history, experience, and observation, of Mr. David Copperfield the Younger, of Blunderstone House.

2. The Copperfield Records. Being the personal history, experience, and observation, of Mr. David Copperfield the Younger, of Copperfield Cottage.

3. The Last Living Speech and Confession of David Copperfield Junior, of Blunderstone Lodge, who was never executed at the Old Bailey. Being his personal history found among his papers.

4. The Copperfield Survey of the World as it Rolled. Being the personal history, experience, and observation, of David Copperfield the Younger, of Blunderstone Rookery.

5. The Last Will and Testament of Mr. David Copperfield. Being his personal history left as a legacy.

6. Copperfield, Complete. Being the whole personal history and experience of Mr. David Copperfield of Blunderstone House, which he never meant to be published on any account.

Or, the opening words of No. 6 might be Copperfield’s Entire; and The Copperfield Confessions might open Nos. 1 and 2. Now, what say you?”

What I said is to be inferred from what he wrote back on the 28th. “The Survey has been my favourite from the first. Kate picked it out from the rest, without my saying anything about it. Georgy too. You hit upon it, on the first glance. Therefore I have no doubt that it is indisputably the best title; and I will stick to it.”

There was a change nevertheless. His completion of the second chapter defined to himself, more clearly than before, the character of the book; and the propriety of rejecting everything not strictly personal from the name given to it. The words proposed, therefore, became ultimately these only:

“The Personal History, Adventures, Experience, and Observation of David Copperfield the Younger, of Blunderstone Rookery, which he never meant to be published on any account.”

And the letter which told me that with this name it was finally to be launched on the first of May, told me also (19th April) the difficulties that still beset him at the opening.

Gosh! What a different novel this might have been! The autobiographical fragments may still have been present, but all those names which David is called throughout the novel: David, Davy, Mas’r Davy, Daisy, Doady, Copperfield, Master Copperfield (I should say Mister!) Master Copperfull, Trot and Trotwood… these could never have been if, instead of David Copperfield and Betsey Trotwood, it told the story of Thomas Mag and his Great Aunt Margaret Something-or-other!

So, having started with novel number 8, I shall now jump back to the beginning and consider the rest in their proper order (I did initially have a silly notion of proceeding in reverse)

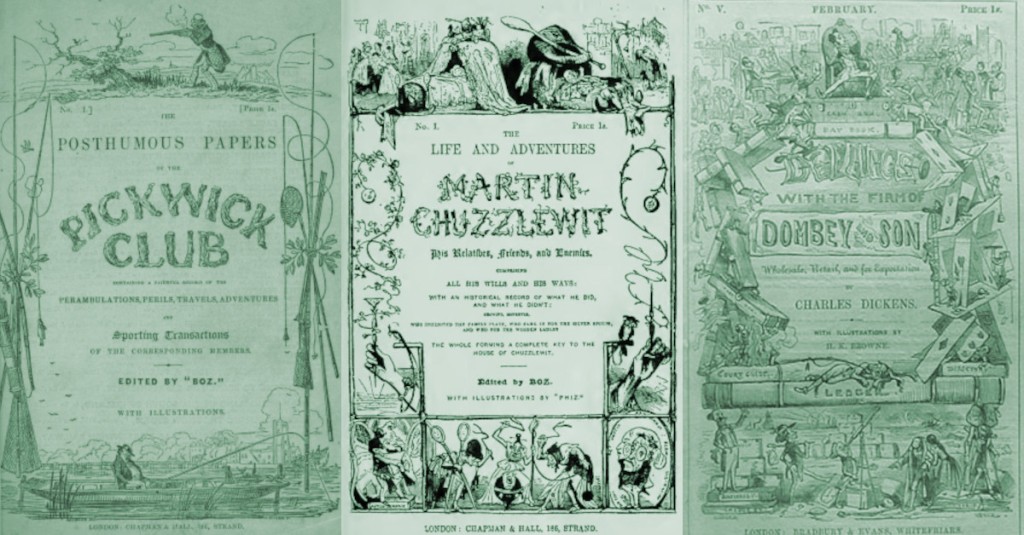

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club

In the initial proposal of the form the novel would take, illustrator Robert Seymour had the notion of ‘The Nimrod Club‘ being the club which was to feature in the ‘sporting plates’

Dickens visited Bath in 1835 and it is there he would have become acquainted with one Moses Pickwick, stagecoach and innkeeper of the White Hart Inn. It is almost certain that this gentleman provided the surname of the novels hero.

A passage from the novel itself acknowledges the connection. In Chapter 35 the club members and Sam are embarking on a journey to the White Hart Inn in Bath:

Mr. Tupman and Mr. Snodgrass had seated themselves at the back part of the coach; Mr. Winkle had got inside; and Mr. Pickwick was preparing to follow him, when Sam Weller came up to his master, and whispering in his ear, begged to speak to him, with an air of the deepest mystery. ‘Well, Sam,’ said Mr. Pickwick, ‘what’s the matter now?’ ‘Here’s rayther a rum go, sir,’ replied Sam. ‘What?’ inquired Mr. Pickwick. ‘This here, Sir,’ rejoined Sam. ‘I’m wery much afeerd, sir, that the properiator o’ this here coach is a playin’ some imperence vith us.’ ‘How is that, Sam?’ said Mr. Pickwick; ‘aren’t the names down on the way-bill?’ ‘The names is not only down on the vay-bill, Sir,’ replied Sam, ‘but they’ve painted vun on ‘em up, on the door o’ the coach.’ As Sam spoke, he pointed to that part of the coach door on which the proprietor’s name usually appears; and there, sure enough, in gilt letters of a goodly size, was the magic name of Pickwick! ‘Dear me,’ exclaimed Mr. Pickwick, quite staggered by the coincidence; ‘what a very extraordinary thing!’ ‘Yes, but that ain’t all,’ said Sam, again directing his master’s attention to the coach door; ‘not content vith writin’ up “Pick-wick,” they puts “Moses” afore it, vich I call addin’ insult to injury, as the parrot said ven they not only took him from his native land, but made him talk the English langwidge arterwards.’ ‘It’s odd enough, certainly, Sam,’ said Mr. Pickwick; ‘but if we stand talking here, we shall lose our places.’

Not to lose OUR places we should resume our journey and note that this novel has always had the two shorter titles by which it is known:

The Pickwick Papers

AND

The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club

the extended descriptive title of which is:

The Posthumous Papers of The Pickwick Club Containing a Faithful Record of the Perambulations, Perils, Travels, Adventures and Sporting Transactions of the Corresponding Members

Oliver Twist

During serial publication in Bentley’s Miscellany the title was:

Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy’s Progress

‘The Parish Boy’s Progress‘ was dropped for early editions in Book format and the novel was titled simply

Oliver Twist

In some later editions the title was expanded to

The Adventures of Oliver Twist

so nothing too complicated or unwieldy here 😀

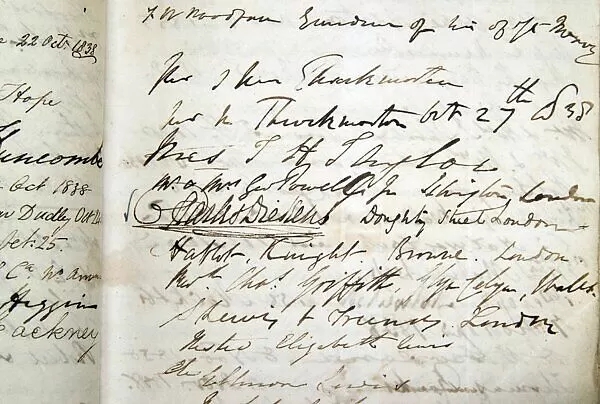

The announcement, in the final monthly issue of The Pickwick Papers, of the serial publication of Dickens’ third novel. Nicholas Nickleby

The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby

or to give it the full descriptive title:

The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby Containing a Faithful Account of the Fortunes, Misfortunes, Uprisings, Downfallings, and Complete Career of the Nickleby Family

Master Humphrey’s Clock — a brief digression

Digressions, incontestably, are the sunshine;——they are the life, the soul of reading!

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman — Laurence SterneWherein we find a bit of context for the next 2 novels which I trust will assist in the determination of how they came to be named as they were.

The Old Curiosity Shop and Barnaby Rudge were both serially published as part of Master Humphrey’s Clock, the weekly periodical edited and written entirely by Charles Dickens and published from 4 April 1840 to 4 December 1841.

While we are meandering here it might be helpful to allow Dickens to explain in his own words his initial concept for how the periodical was to work:

I have a notion of this old file in the queer house, opening the book by an account of himself, and, among other peculiarities, of his affection for an old quaint queer-cased clock; showing how that when they have sat alone together in the long evenings, he has got accustomed to its voice, and come to consider it as the voice of a friend; how its striking, in the night, has seemed like an assurance to him that it was still, a cheerful watcher at his chamber-door; and now its very face has seemed to have something of welcome in its dusty features, and to relax from its grimness when he has looked at it from his chimney-corner. Then I mean to tell how that he has kept odd manuscripts in the old, deep, dark, silent closet where the weights are; and taken them from thence to read (mixing up his enjoyments with some notion of his clock); and how, when the club came to be formed, they, by reason of their punctuality and his regard for this dumb servant, took their name from it. And thus I shall call the book either Old Humphrey’s Clock, or Master Humphrey’s Clock; beginning with a woodcut of old Humphrey and his clock, and explaining the why and wherefore. All Humphrey’s own papers will be dated then From my clock-side, and I have divers thoughts about the best means of introducing the others.

— The Life of Charles Dickens by John Forster

The Old Curiosity Shop

The Old Curiosity Shop is the only one of the first eight novels which does not contain the name (or part of the name) of a central character in the work. It is also one of only two of the novels which are named after a location (which may be interpreted as a building) Bleak House being the other— One could argue that A Tale of Two Cities is also named after (implied) locations, but neither London nor Paris could be thought of as a single premises.

In February 1840, Charles Dickens and his wife, Catherine, Daniel Maclise and John Forster visited Walter Landor in Bath. Of this visit Forster states, “it was during three happy days we passed together there that the fancy which was shortly to take the form of Little Nell first occurred to its author—but as yet with the intention only of making out of it a tale of a few chapters.”

How this ‘tale of a few chapters’ became the fourth full-length novel of the Inimitable is best told by John Forster – with a little help from Dickens himself:

On the 1st of March we returned from Bath; and on the 4th I had this letter: “If you can manage to give me a call in the course of the day or evening, I wish you would. I am laboriously turning over in my mind how I can best effect the improvement we spoke of last night, which I will certainly make by hook or by crook, and which I would like you to see before it goes finally to the printer’s. I have determined not to put that witch-story into number 3, for I am by no means satisfied of the effect of its contrast with Humphrey. I think of lengthening Humphrey, finishing the description of the society, and closing with the little child-story, which is sure to be effective, especially after the old man’s quiet way.”

Then there came hard upon this: “What do you think of the following double title for the beginning of that little tale? ‘Personal Adventures of Master Humphrey: The Old Curiosity Shop.’ I have thought of Master Humphrey’s Tale, Master Humphrey’s Narrative, A Passage in Master Humphrey’s Life—but I don’t think any does as well as this. I have also thought of The Old Curiosity Dealer and the Child instead of The Old Curiosity Shop. Perpend. Topping waits.”

—And thus was taking gradual form, with less direct consciousness of design on his own part than I can remember in any other instance of all his career, a story which was to add largely to his popularity, more than any other of his works to make the bond between himself and his readers one of personal attachment, and very widely to increase the sense entertained of his powers as a pathetic as well as humorous writer.

He had not written more than two or three chapters, when the capability of the subject for more extended treatment than he had at first proposed to give to it pressed itself upon him, and he resolved to throw everything else aside, devoting himself to the one story only. There were other strong reasons for this. Of the first number of the Clock nearly seventy thousand were sold; but with the discovery that there was no continuous tale the orders at once diminished, and a change must have been made even if the material and means for it had not been ready. There had been an interval of three numbers between the first and second chapters, which the society of Mr. Pickwick and the two Wellers made pleasant enough; but after the introduction of Dick Swiveller there were three consecutive chapters; and in the continued progress of the tale to its close there were only two more breaks, one between the fourth and fifth chapters and one between the eighth and ninth, pardonable and enjoyable now for the sake of Sam and his father. The reintroduction of these old favorites, it will have been seen, formed part of his original plan; of his abandonment of which his own description may be added, from his preface to the collected edition:

“The first chapter of this tale appeared in the fourth number of Master Humphrey’s Clock, when I had already been made uneasy by the desultory character of that work, and when, I believe, my readers had thoroughly participated in the feeling. The commencement of a story was a great satisfaction to me, and I had reason to believe that my readers participated in this feeling too. Hence, being pledged to some interruptions and some pursuit of the original design, I set cheerfully about disentangling myself from those impediments as fast as I could; and, this done, from that time until its completion The Old Curiosity Shop was written and published from week to week, in weekly parts.”

Barnaby Rudge

Dickens’ fifth novel and the first of his historical novels, centred around the 1780 anti-Catholic Gordan Riots, was perhaps the first novel which the author had a conception for. A contract was signed in 1836 while he was writing Pickwick for the work to be published, like Oliver Twist, serially in Bentley’s Miscellany (as announced in the image above) – this did not happen. Rather than go into the full history here, the reasons for delay (and more) may be found in this excellent article in The Guardian by Peter Ackroyd (as a biographer of Dickens, he certainly knows his stuff!)

In 1836 the provisional title for the novel was:

Gabriel Varden – The Locksmith of London

five years later the title had found its final form, which in its full version is

Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of Eighty

Martin Chuzzlewit

The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit

or to give it the full descriptive title:

The Life and Adventures

of

Martin Chuzzlewit

His Relatives, Friends, and Enemies.

Comprising

All His Wills and His Ways.

With an Historical Record of what he did and what he didn’t

Shewing moreover

Who inherited the family plate, who came in for the silver spoons,

and who came in for the wooden ladles.

The whole forming a complete key to the

House of Chuzzlewit.which I believe makes it the longest of the full descriptive titles. On a personal note, I love the ‘what he did and what he didn’t’ 😀

The name Martin Chuzzlewit was finally settled upon, as Forster states, ‘only after much deliberation, as a mention of his changes will show. Martin was the prefix to all, but the surname varied from its first form of Sweezleden, Sweezleback, and Sweezlewag, to those of Chuzzletoe, Chuzzleboy, Chubblewig, and Chuzzlewig; nor was Chuzzlewit chosen at last until after more hesitation and discussion. What he had sent me in his letter as finally adopted, ran thus: “The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewig, his family, friends, and enemies. Comprising all his wills and his ways. With an historical record of what he did and what he didn’t. The whole forming a complete key to the house of Chuzzlewig.” All which latter portion of the title was of course dropped as the work became modified, in its progress, by changes at first not contemplated;’ — The Life of Charles Dickens by John Forster

Dombey and Son

Full title:

Dealings with the Firm of Dombey and Son: Wholesale, Retail and for Exportation.

or for short:

Dombey and Son

…which is all well and good in its way, but the book is really about Florence! after all, as Miss Tox says:

“Dear me, dear me! To think that Dombey and Son should be a Daughter after all!”

Thanks for reading 😀

-

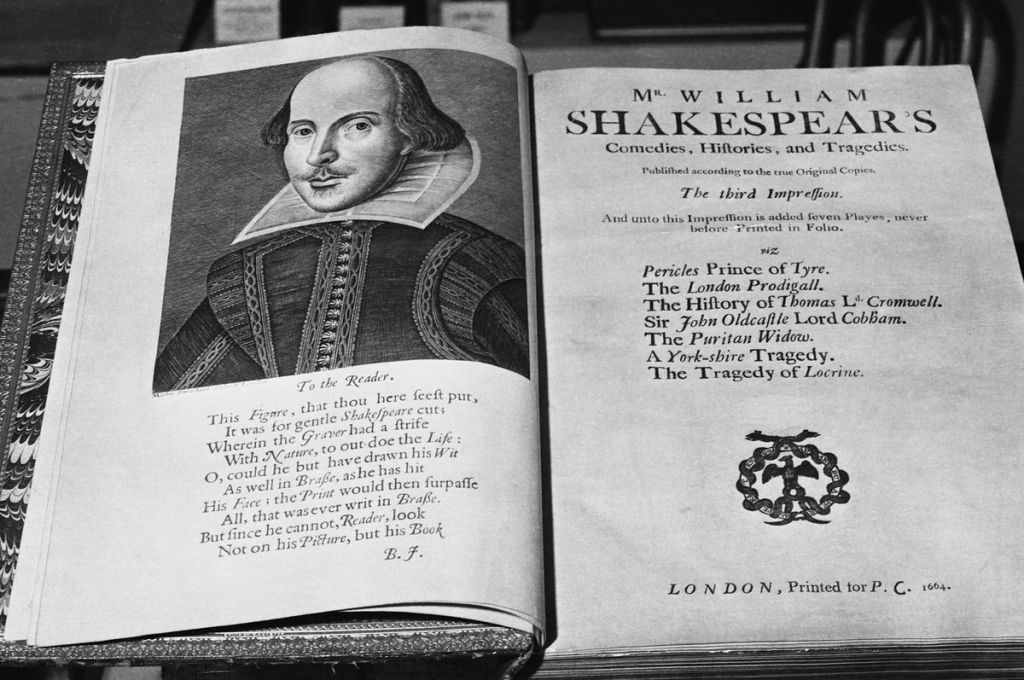

Charles Dickens — Favourite quotes from Shakespeare.

From the few posts I have managed on this blog so far, two things may be safely surmised:

- That I am something of a big Shakespeare fan

- That I am something of a big Dickens fan

To put an end to doubt, I can positively confirm both these impeachments

But, enough about me… The real question here is, ‘Was Charles Dickens something of a big Shakespeare fan?’

In order to get to the bottom of this, I treated my self to a very interesting and informative book:

Shakespeare & Dickens: The dynamics of influence by Valerie L Gager (1996)

An absolutely fascinating read, I can assure you, especially if, like me, you are something of a Shakespeare fan and something of a Dickens fan!

Theatre Royal, Star Hill, Rochester From boyhood visits to the local Theatre between the ages of 5 & 9 to see Richard III and Macbeth, to the quote from Romeo and Juliet written in a letter the day before he died, the author traces the many intersections between the works of Shakespeare and the life and works of Charles Dickens.

“These violent delights have violent ends”

quoted in letter to William Charles Kent — 8th June 1870My feeling from what I have read so far, and from my spotting of the occasional Shakespearean allusions and references in the novels, that the answer to the question, ‘Was Charles Dickens something of a big Shakespeare fan?’ is a resounding ‘YES!’

I must also add that I am grateful to this wonderful book, and especially its author, for some of the discoveries listed in this post. (Not all of them. I did manage to find many of them all by myself before I even bought the book — Just so you know!)

No doubt Dickens had a favourite quote and a favourite play by Shakespeare — it would take a good deal of detective work to even make an educated guess at such things – perhaps even beyond the investigative prowess of Mr. Bucket. I cannot even definitively say which would be my favourite quote or favourite play.

I generally say that my favourite play is Twelfth Night, but every time I DO say it I immediately begin to doubt whether I actually believe myself or not!

It is the same with a favourite quote (among many, many favourite quotes) If I were forced to choose I suppose I would say:

Alas, our frailty is the cause, not we!

Viola. Twelfth Night II(ii)

For such as we are made of, such we be.But there are so many good ones that I’d rather not be forced to choose if it’s quite alright with everyone! ‘Thanks for that.’ —as Macbeth memorably says in the banquet scene of the play of the same name!

Turning now to speculations about which might have been Charles Dickens’ favourite Shakespeare play, some apprentice level detective work would uncover that the plays Hamlet and Macbeth generally crop up the most throughout the works, letters and speeches. It does not necessarily follow, however, that either of these great plays was his favourite.

Regarding quotes, most fans of Shakespeare will have a veritable library of favourites suiting all manner of forms, moods and occasions. Charles Dickens, as surmised above, being a big fan of Shakespeare was no doubt the same. While we cannot with any certainty arrive at his favourite favourite, we can find many quotes from which he took inspiration drawn from those famous plays of the Bard of Avon.

A few examples might be nice, what! Well… alrighty then:

In 1844 writing to his friend John Forster to inform him that he had finally settled upon a title for his second Christmas book, he sent a letter ‘in which not a syllable was written but “We have heard THE CHIMES at midnight, Master Shallow!”‘ — a direct quote of Falstaff’s line from Henry IV Part 2

If you want the quote in context, here is a little excerpt from that scene of the play in a Dress Rehearsal Run in Cambridge. (No idea who the chap playing Falstaff is!!)

The titles of the two weekly journals, Household Words (1850 – 1859) and All The Year Round (1859 – 1895) were inspired by passages from Shakespeare.

The first is taken from the St. Crispin’s Day speech from Act 4 of Henry V:

...then shall our names. Familiar in his mouth as household words Harry the king, Bedford and Exeter, Warwick and Talbot, Salisbury and Gloucester, Be in their flowing cups freshly remember'd.

The second finds its source in a passage from Act 1 of Othello:

Her father loved me; oft invited me; Still question'd me the story of my life, From year to year, the battles, sieges, fortunes, That I have passed.

In both cases the wording of the original quote is slightly changed to suit its purpose, yet the source is still recognisable.

There are many ways in which the words of Shakespeare provide inspiration for the writings of Dickens – from direct quotation and overt reference through allusions and transformations to the very faintest of echoes.

T. S. Eliot, whose poem The Waste Land is jam-packed with allusions from a wide range of sources – literary and otherwise, has this to say on literary ‘borrowing’

One of the surest of tests is the way in which a poet borrows. Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different. The good poet welds his theft into a whole of feeling which is unique, utterly different from that from which it was torn; the bad poet throws it into something which has no cohesion. A good poet will usually borrow from authors remote in time, or alien in language, or diverse in interest.

T. S. Eliot “Phillip Massinger” Times Literary Supplement 27/5/1919I would certainly put Dickens in the category of a ‘good poet.’ There is so much of the poetic in his prose after all.

O for a muse of fire

There is one quote from Henry V which hints its influence as early as 1837, cropping up from time to time over the course of 3 decades (latest ‘confirmed’ sighting in 1867)— appearing in novels, letters, speeches, prefaces— in recognisable wording or in skilful transformations of ‘the pith and marrow of [its] attribute’ (as Hamlet might say!)

There is some soul of goodness in things evil,

Henry V – Act 1 Scene 4

Would men observingly distil it out.In the Preface to the 3rd edition of Oliver Twist (1841) Dickens writes:

I confess I have yet to learn that a lesson of the purest good may not be drawn from the vilest evil. I have always believed this to be a recognised and established truth, laid down by the greatest men the world has ever seen, constantly acted upon by the best and wisest natures, and confirmed by the reason and experience of every thinking mind.

The first sentence is the essence of the quote from Henry V, and undoubtedly Shakespeare would be among the greatest men the world has ever seen who laid down recognised and established truth(s)

What follows is a selection of quotes in chronological order which have their source of inspiration in the quote or in its essence. Starting with an universally recognised excellent, succinct and beautiful sentiment from…

The Pickwick Papers (1837)

There are dark shadows on the earth, but its lights are stronger in the contrast. (Chapter 57)

Nicholas Nickleby (1838)

There are shades in all good pictures, but there are lights too, if we choose to contemplate them. (Chapter 6)

which finds a transformed, and no less beautifully stated version in…

Oliver Twist (1838)

Men who look on nature, and their fellow-men, and cry that all is dark and gloomy, are in the right; but the sombre colours are reflections from their own jaundiced eyes and hearts. The real hues are delicate, and need a clearer vision. (Chapter 34)

I pause here for a quick note. It would appear that I got the order wrong with the above two examples. Oliver Twist was the 2nd Novel and Nicholas Nickleby followed it. But as both novels overlapped during the serial publication Chapter 6 of Nicholas Nickleby appeared in April 1838 while Chapter 34 of Oliver Twist appeared in June 1838.

While we are thus paused, It is probably worth mentioning that in 1839 the celebrated Victorian actor, William Charles Macready (and notable thespian pal of Dickens) was performing in the title role of Henry V and that Dickens attended rehearsals of the production as well as seeing it in performance during this year. This is pertinent because our next item just happens to be a…

Letter to W. C. Macready – 17 August 1840

‘I have found the soul of goodness in this evil thing at all events, and when I think of all you said and did, I would not recall (if I had the power) one atom of my passion and intemperance, which carried with it a breath of yours’

[The context here is apparently that Charles Dickens and John Forster had a bit of a falling out and Macready, acting as peacemaker effectively told them to ‘kiss and make up]

Speech: Edinburgh. June 25th 1841

[At a public dinner, given in honour of Mr. Dickens, and presided over by the late Professor Wilson, the Chairman having proposed his health in a long and eloquent speech, Mr. Dickens returned his thanks.]

Full speech may be read at The Circumlocution Office

“It is a difficult thing for a man to speak of himself or of his works. But perhaps on this occasion I may, without impropriety, venture to say a word on the spirit in which mine were conceived. I felt an earnest and humble desire, and shall do till I die, to increase the stock of harmless cheerfulness. I felt that the world was not utterly to be despised; that it was worthy of living in for many reasons. I was anxious to find, as the Professor has said, if I could, in evil things, that soul of goodness which the Creator has put in them.“

Another brief pause before moving back into ‘novel’ territory. I am including an extended passage for the next one to show how skilfully Dickens blends the inspiration source concept with the surrounding ideas and tone of the narrative. I make no apologies for doing so for a number of reasons

- I find the paragraphs beautifully written

- Barnaby Rudge deserves more love than it gets because it’s brilliant

- I mean, there’s a talking Raven!

- What more could you want?

- Not even William Shakespeare had a talking raven! —

- Hamlet‘s ‘croaking raven doth bellow for revenge’

- The ‘raven himself is hoarse that croaks the fatal entrance of Duncan under Lady Macbeth‘s battlements’

- In A Midsummer Night’s Dream Lysander believes there are none ‘who would not change a raven for a dove’

- Juliet oxymoronically apostrophises her Romeo as a ‘Dove-feather’d raven’

- But not one of them talks like Barnaby’s raven, Grip

Barnaby Rudge (1841)

In the exhaustless catalogue of Heaven’s mercies to mankind, the power we have of finding some germs of comfort in the hardest trials must ever occupy the foremost place; not only because it supports and upholds us when we most require to be sustained, but because in this source of consolation there is something, we have reason to believe, of the divine spirit; something of that goodness which detects amidst our own evil doings, a redeeming quality; something which, even in our fallen nature, we possess in common with the angels; which had its being in the old time when they trod the earth, and lingers on it yet, in pity.

How often, on their journey, did the widow remember with a grateful heart, that out of his deprivation Barnaby’s cheerfulness and affection sprung! How often did she call to mind that but for that, he might have been sullen, morose, unkind, far removed from her—vicious, perhaps, and cruel! How often had she cause for comfort, in his strength, and hope, and in his simple nature! Those feeble powers of mind which rendered him so soon forgetful of the past, save in brief gleams and flashes,—even they were a comfort now. The world to him was full of happiness; in every tree, and plant, and flower, in every bird, and beast, and tiny insect whom a breath of summer wind laid low upon the ground, he had delight. His delight was hers; and where many a wise son would have made her sorrowful, this poor light-hearted idiot filled her breast with thankfulness and love. (Chapter 47)

Martin Chuzzlewit (1844)

[Old Martin Chuzzlewit is in the process of giving Pecksniff a piece of his mind, having a little while before ‘struck him down upon the ground.’]

‘Once resolved to try him, I was resolute to pursue the trial to the end; but while I was bent on fathoming the depth of his duplicity, I made a sacred compact with myself that I would give him credit on the other side for any latent spark of goodness, honour, forbearance—any virtue—that might glimmer in him. For first to last there has been no such thing. Not once. He cannot say I have not given him opportunity. He cannot say I have ever led him on. He cannot say I have not left him freely to himself in all things; or that I have not been a passive instrument in his hands, which he might have used for good as easily as evil. Or if he can, he Lies! And that’s his nature, too.’ (Chapter 52)

The description for Chapter 52 being, ‘IN WHICH THE TABLES ARE TURNED, COMPLETELY UPSIDE DOWN’ it is interesting to note that this passage in relation to the Henry V quote is turned somewhat upside down – Old Martin looks but finds no soul of goodness in things Pecksniffian and duplicitous!

Household Words – Issue 1 – 30 March 1850

A preliminary word…

This, the very first article of Household Words also has quotes from The Tempest and As You Like It (which you may spot in the image below)

Little Dorrit (1856)

[it’s in here somewhere – conversation between the landlady of the Break of Day and a tall Swiss belonging to the church]

‘Ah Heaven, then,’ said she. ‘When the boat came up from Lyons, and brought the news that the devil was actually let loose at Marseilles, some fly-catchers swallowed it. But I? No, not I.’

‘Madame, you are always right,’ returned the tall Swiss. ‘Doubtless you were enraged against that man, madame?’

‘Ay, yes, then!’ cried the landlady, raising her eyes from her work, opening them very wide, and tossing her head on one side. ‘Naturally, yes.’

‘He was a bad subject.’

‘He was a wicked wretch,’ said the landlady, ‘and well merited what he had the good fortune to escape. So much the worse.’

‘Stay, madame! Let us see,’ returned the Swiss, argumentatively turning his cigar between his lips. ‘It may have been his unfortunate destiny. He may have been the child of circumstances. It is always possible that he had, and has, good in him if one did but know how to find it out.’

(Chapter 11)

Oliver Twist Charles Dickens Edition (1867)

Descriptive headings were added to pages of the text. Chapter 16 contains the following heading:

That’s all I can find. There may be more. If you can think of any more which might relate to the original Shakespeare quote, please pop a comment down below 😀

There is some soul of goodness in things evil,

Henry V – Act 1 Scene 4

Would men observingly distil it out.It’s a great quote. It’s quite clear that Charles Dickens was fond of it. But whether it was his favourite Shakespeare quote or not we shall never know.

Thanks for reading 😀

-

Dickens Character Spotlight – Susan Nipper – Dombey and Son

One good character by Dickens requires all eternity to stretch its legs in.

G.K. ChestertonOne of my Favourite things about reading Dickens is his talent for creating vividly drawn, memorable characters. The variety of his invention in this regard is staggering. Dombey and Son, like the rest of his novels, contains many wonderful characters – among them all my favourite is Susan Nipper, Florence Dombey’s nurse-maid, companion and friend. A true-hearted comic character and the possessor of a wonderful character arc. What follows in this post will not so much be a character analysis – that seems too much like a school assignment, and I haven’t done those since I was at school! It will be, rather, some collected thoughts and observations, amounting to a celebration of this wonderful character. It’s bound to be a somewhat long post, so I’ll try and make sure I break it up with some nice pictures from time to time!

As I have recorded audiobook versions of many of Dickens’ works (mainly the shorter ones, it must be confessed, but they are quite long) I have spent a good deal of time contemplating character as created by Mr D. Having at my disposal only a finite number of ways to vocally characterise the cast of a novel, I often use the similarities between characters in different works as a starting point. So, for example, Mr Bumble’s feelings of self-importance (Oliver Twist being the first of my Dickens audiobook recordings) have been a building block for such characters as Bounderby (Hard Times); Stryver (A Tale of Two Cities); Pumblechook (Great Expectations); and Wackford Squeers (Nicholas Nickleby) to name but a few! It has become my way, even in private reading to mine these sort of inter-character connections or reminders. But also in acting work, when considering character, one pulls from multiple sources when trying to build a character: when I was playing the main character in Chekhov’s Ivanov I actually found Sydney Carton to be a great help in trying to build a conception of a man who is tired of life.

Susan Nipper is such a well constructed character that she has elements, suggestions or reminders in her particular constitution, that stretch back through the previous novels and yet point forward to elements of characters yet to come.

I am far from alone in my admiration of the Nipper. The critic G.K. Chesterton regarded her as ‘one of the greatest of Dickens’s achievements.’

Susan Nipper is a young person after Dickens’s heart, in her habits of speech suggesting a shrill feminine echo of Sam Weller, and morally a pattern of all virtues, all the proprieties’

The Immortal Dickens – George GissingAnd as for the writer himself:

In July 1846, Charles Dickens sent the manuscript of the first 4 chapters of Dombey and Son to his friend, and biographer, John Forster, with an outline of his immediate intentions in reference to Dombey.

I shall rely very much on Susan Nipper grown up, and acting partly as Florence’s maid, and partly as a kind of companion to her, for a strong character throughout the book.

The Life of Charles Dickens by John Forster. Volume 2And in this intention, I for one, would say he thoroughly succeeded!

A Most Notable Appearance is Made Upon the Stage of these Adventures:

“Oh well, Miss Floy! And won’t your Pa be angry neither!” cried a quick voice at the door, proceeding from a short, brown, womanly girl of fourteen, with a little snub nose, and black eyes like jet beads. “When it was “tickerlerly given out that you wasn’t to go and worrit the wet nurse.”

When Susan, first bursts into the story in Chapter 3, we immediately get the sense of a character, quite unlike any we have met so far. All of whom have, in their way, paid the requisite homage and deference to the great name of Dombey, and conducted themselves in accordance with the sad nature of the events thus far.

Not so with this new actor upon the Dombey stage: ‘the black-eyed girl, who was so desperately sharp and biting that she seemed to make one’s eyes water.’ She feels like a fresh burst of energy into the desolate and sombre house. And before we learn her name she has been referred to as the sharp girl and Spitfire. The content and delivery of her speech shows her to be of the lower orders and in some way connected with the management and care of six-year old Florence.

Spitfire made use of none but comma pauses; shooting out whatever she had to say in one sentence, and in one breath, if possible.

As to Florence… it was established in chapter 1 that to her father’s mind, Florence did not have a ‘destiny’ to accomplish like her little brother, Paul, because ‘what was a girl to Dombey and Son! In the capital of the House’s name and dignity, such a child was merely a piece of base coin that couldn’t be invested—a bad Boy—nothing more.’

The propitiators of Mr Dombey’s magnificence will not gainsay or controvert this opinion.

To Florence’s mother, her ‘little voice’ was ‘familiar and dearly loved’ but she too had most likely submitted to the will and opinion of Dombey along with the rest.

Susan, however, in her plain speaking of the truth of Florence’s plight, has no concern of it reflecting unfavourably on Mr Dombey, and importantly identifies herself as a non-flatterer in the household. While much in her first presentation to the reader is done in a humorous way, this aspect of her character has a serious function in the ongoing narrative – at least I think so, but more on this later:

“She’ll be quite happy, now she has come home again,” said Polly, nodding to her with an encouraging smile upon her wholesome face, “and will be so pleased to see her dear Papa tonight.”

“Lork, Mrs Richards!” cried Miss Nipper, taking up her words with a jerk. “Don’t. See her dear Papa indeed! I should like to see her do it!”

“Won’t she then?” asked Polly.

“Lork, Mrs Richards, no, her Pa’s a deal too wrapped up in somebody else, and before there was a somebody else to be wrapped up in she never was a favourite, girls are thrown away in this house, Mrs Richards, I assure you.”

The child looked quickly from one nurse to the other, as if she understood and felt what was said.

“You surprise me!” cried Polly. “Hasn’t Mr Dombey seen her since—”

“No,” interrupted Susan Nipper. “Not once since, and he hadn’t hardly set his eyes upon her before that for months and months, and I don’t think he’d have known her for his own child if he had met her in the streets, or would know her for his own child if he was to meet her in the streets to-morrow, Mrs Richards, as to me,” said Spitfire, with a giggle, “I doubt if he’s aweer of my existence.”

“Pretty dear!” said Richards; meaning, not Miss Nipper, but the little Florence.

“Oh! there’s a Tartar within a hundred miles of where we’re now in conversation, I can tell you, Mrs Richards, present company always excepted too,” said Susan Nipper; “wish you good morning, Mrs Richards, now Miss Floy, you come along with me, and don’t go hanging back like a naughty wicked child that judgments is no example to, don’t!”

In spite of her somewhat rough handling of her charge and associated wrenches, and haulings, and transports of coercion, it is clear that there is a strong relationship between Susan and her young Miss Floy.

Spitfire seemed to be in the main a good-natured little body, although a disciple of that school of trainers of the young idea which holds that childhood, like money, must be shaken and rattled and jostled about a good deal to keep it bright. For, being thus appealed to with some endearing gestures and caresses, she folded her small arms and shook her head, and conveyed a relenting expression into her very-wide-open black eyes.

What’s in a name?

(or an epithet for the matter of that!)

Susan Nipper is one of those characters upon whom Dickens affectionately, or humorously, or whimsically bestows numerous names or epithets:

Miss Nipper, Susan, Spitfire, the sharp girl, the black-eyed or the black-eyed girl, the Nipper (presumably as being exemplary of her kind) and of course, Susan Nipper (she does acquire a name change by the end of the novel, but that would constitute a big spoiler to those who have not yet read this wonderful work!)

It is a well known fact that Dickens took great care with the naming of his characters – major and minor. Many of the names being suggestive to the reader of initial character attributes.

Even the lowliest, most fleeting minor character in a Dickens novel, regardless of wealth or education, can have an individual personality and humanity… and it’s interesting how Dickens expertly wields language to do this, in even the smallest degree.

Chi Luu – Charles Dickens and the Linguistic Art of the Minor CharacterThis great article by Chi Luu about Dicken’s naming conventions looks at this aspect of his craft; and for a more in depth look at the same is the comprehensive study, by Elizabeth Hope Gordon (1917) which seems to mention more or less all of the thousand plus characters across his works:

Susan’s surname is quite appropriate to her character as it first appears:

Nipper (n) a thing that nips or bites

The later definition of Nipper meaning a child did not enter use until 1859, but for modern readers there is this connotation too

Nipper also has a nautical definition (in keeping with the Maritime theme in Dombey and Son)

nipper

A short rope used to bind a cable to the “messenger” (a moving line propelled by the capstan) so that the cable is dragged along, too (used where the cable is too large to be wrapped around the capstan itself). During the raising of an anchor, the nippers were attached and detached from the (endless) messenger by the ship’s boys. Hence the term for small boys: “nippers”.

I don’t think it is much of a stretch to say that Susan becomes a figurative ‘anchor’ for her dear, darling Miss Floy.

The Nipper’s first name (and the description of her black eyes) may have called to Victorian readers the poem by John Gay (he of The Beggar’s Opera fame), “Black-eyed Susan”

All in the Downs the fleet was moored, The streamers waving in the wind, When black-eyed Susan came aboard; "O, where shall I my true-love find? Tell me, ye jovial sailors, tell me true If my sweet William sails among the crew.

The rest of the poem can be found here: https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/black-eyed-susan

Here again is a nautical connection – of interest too is the surname of ‘Gay’

Or perhaps the theatre-goers of the time would recall Douglas Jerrold’s three act melodrama, Black-Eyed Susan: or All in the Downs, from 1829

There may be no intended connection here, but as it was a discovery new to myself, I include it… because why not:

Black-eyed Susan is also a type of flower (Rudbeckia hirta). The state flower of Maryland since 1918.

With reference to the above poem, Sweet William is also a flower! (But this was not new knowledge to me)

But, perhaps I digress. Onwards…

The epithet ‘Spitfire’ has an interesting and colourful history – its most immediate meaning here of a person given to outbursts of spiteful temper and anger is the one that prepare’s us best for the initial temperament of Susan.

But since the 1600s the term has also been applied to a canon.

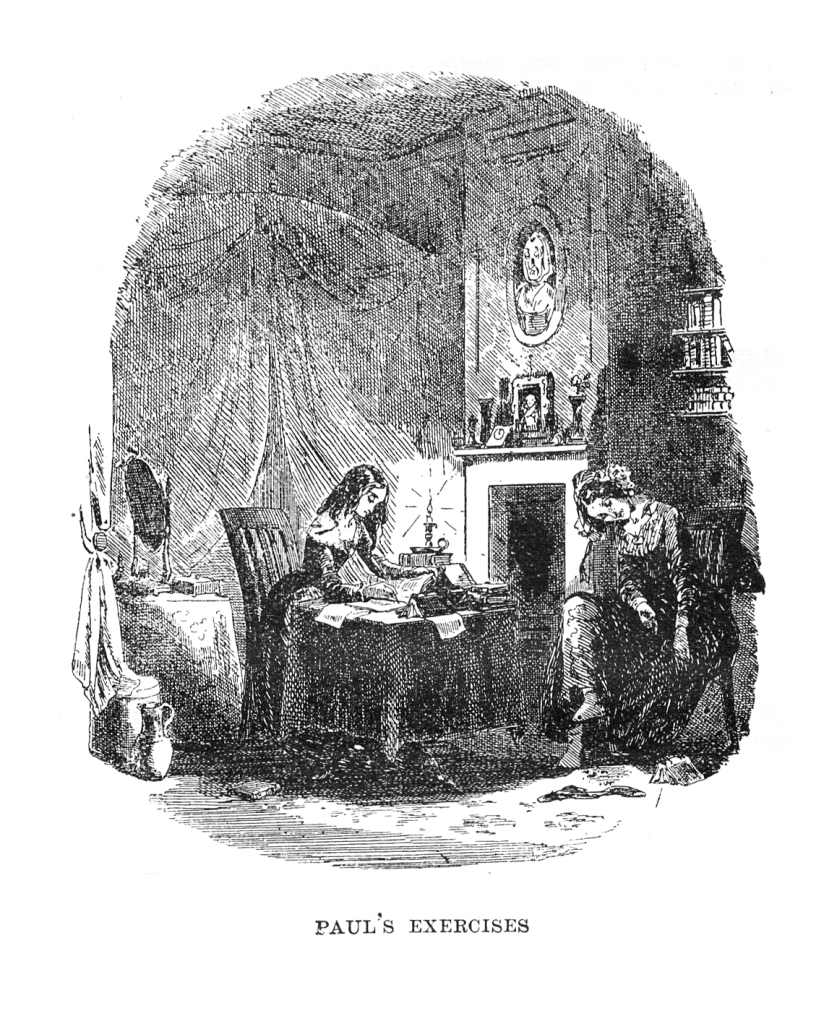

And I love the fact that in this full length illustration by Phiz, there is a picture of an erupting volcano (otherwise spitting fire) on the wall in the background 😊

Spitfire descends from an earlier term shit-fire from the Spanish cacafuego – meaning a blustering, over-confident braggart (Major Joey Bagstock, anyone?). Interesting that there is a nautical connection here too. You can learn more about this fascinating term here: https://www.haggardhawks.com/post/cacafuego

The Function of Spitfire.

Susan is a comic character who provides many moments of delight throughout the novel. But she also adds colour to the more moving and sentimental sections in which she appears,

Susan Nipper remains a purely comic character throughout her speech, and even grows more comic as she goes on. She is more serious than usual in her meaning, but not more serious in her style. Dickens keeps the natural diction of Nipper, but makes her grow more Nipperish as she grows more warm… Whenever he made comic characters talk sentiment comically, as in the instance of Susan, it was a success, but an avowedly extravagant success.

Charles Dickens: A Critical Study – G. K. ChestertonSusan Nipper provides a very important function in terms of the narrative and our response to many aspects of it.

In the article “Jolly” Mark Tapley in Martin Chuzzlewit — one of Dickens’s most popular originals, Phillip V Allingham states with reference to Mark Tapley:

In his judgments, despite his penchant for actively looking for obstacles to his equanimity, Mark serves as Dickens’s normative touchstone: how he feels, implies the author, the reader ought to feel, too. He is therefore more than an updated or retreaded version of the first great Dickens servant-companion, Mr. Pickwick’s valet, the quintessential Cockney, Sam Weller; rather, in a story full of deceptive surfaces, Mark Tapley is, above all and from the first, “honest Mark,” in contrast to the Chuzzlewit toadies and sychophants whom Dickens introduced in the initial instalment

In the same way, Susan Nipper is a touchstone for the reader in Dombey and Son. Her no-nonsense, honest utterances will tell us how we should be regarding many of the characters and events of Dombey’s world. She is one of the forces of good in the novel, and perhaps the character we trust the most. Not only in her words but in her actions are we guided by the author to see the things we should.

So, of the superintendence of Mrs Chick and Miss Tox in the nursery, Susan’s comically explained behaviours give us a powerful sense of the truth of her feeling:

There was anything but solitude in the nursery; for there, Mrs Chick and Miss Tox were enjoying a social evening, so much to the disgust of Miss Susan Nipper, that that young lady embraced every opportunity of making wry faces behind the door. Her feelings were so much excited on the occasion, that she found it indispensable to afford them this relief, even without having the comfort of any audience or sympathy whatever. As the knight-errants of old relieved their minds by carving their mistress’s names in deserts, and wildernesses, and other savage places where there was no probability of there ever being anybody to read them, so did Miss Susan Nipper curl her snub nose into drawers and wardrobes, put away winks of disparagement in cupboards, shed derisive squints into stone pitchers, and contradict and call names out in the passage.

And again with Miss Tox:

Miss Nipper, in her burning zeal, disparaged Miss Tox as a crocodile; yet her sympathy seemed genuine, and had at least the vantage-ground of disinterestedness—there was little favour to be won by it.

In the Midshipman when Susan is biting her bonnet string and sharing private emotion with the skylight, our attention is focussed more sharply on the conversation between Walter and Florence and Uncle Sol that is making her act that way.

And when Susan in one admirable scene says what she would say to ‘some and all’ she is perhaps the most satisfactory representative of all the characters to say what has so long needed to be said. It is our cultivated connection to her as our touchstone that increases our admiration in her act. In our secret hearts, we know she is the best person to have said it!

Antecedents, Associations, and Nippers Yet to Come!

I love when reading Dickens of the many ways in which characters or events call forth associations from elsewhere in his writing. The way in which characters are presented is always masterfully done, they always feel like unique creations and yet many of their ingredients are the same. ‘Whiffs and flavours’ of character, as a member of the Dickens Club memorably stated it.

I must mention Susan Nipper, the nurse of Florence Dombey. Susan begins well on the pattern of her class; she is snappy, and brief-tempered, fond of giving smacks and pulling hair; one sees no reason why with favouring circumstances she should not develop into a nagger of distinction. But something is observable in her which imposes caution on prophecy; we see that Susan, though a mere domestic, has a very unusual endowment of wit; she is sharp in retort, but also in perception; in any case she cannot become a mere mouthing idiot. In course of time we see that she has a good heart. And so it comes to pass that, in spite of origin and evil example, the girl grows in grace. She is fortunately situated; her sweet young mistress does her every kind of good;

Charles Dickens: A Critical Study (1898) – George GissingGissing’s observation above has many elements that could be applied to both of the Gents pictured above. Sam Weller from The Pickwick Papers, and Dick Swiveller from The Old Curiosity Shop. In common with both, Susan has an exuberant eloquence which is all her own, in addition to the loyalty, devotion and companionship of the three to Pickwick, The Marchioness and Florence.

There are pairings from the other earlier Novels too which exhibit similar degrees of faithful and loyal companionship. Nicholas Nickleby and Smike, Jolly Mark Tapley and Martin Chuzzlewit, which lend some of their whiffs and flavours to the unique recipe of Miss Susan Nipper.

(I have yet to read Barnaby Rudge, and I actually feel really bad that I have missed it out of the sequence

But If I had to speculate on a character who was an antecedent to Susan, my money would be on Grip the Raven!)

‘Call him!’ echoed Barnaby, sitting upright upon the floor, and staring vacantly at Gabriel, as he thrust his hair back from his face. ‘But who can make him come! He calls me, and makes me go where he will. He goes on before, and I follow. He’s the master, and I’m the man. Is that the truth, Grip?’

The raven gave a short, comfortable, confidential kind of croak;—a most expressive croak, which seemed to say, ‘You needn’t let these fellows into our secrets. We understand each other. It’s all right.’

Barnaby Rudge – Chapter 6Yes! That seems Nipperish enough!

Captain Cuttle’s admiration of the ‘desperate courage of the fair’ Susan in her clam that she would ‘stop’ Mrs MacStinger, shows that Susan, in common with Sam Weller (and his progenitor, Tony Weller too) might have pugilistic tendencies!

Mix in too some of the heart and tenacity of Nancy (Oliver Twist), the simple homely duty and attention of Ruth Pinch (Martin Chuzzlewit) and a dash of the charm and hard work of Mary, the pretty housemaid (The Pickwick Papers)

The mention of black eyes calls to mind Arabella Allen from The Pickwick Papers: that young lady with black eyes, and arch smile, and a pair of remarkably nice boots with fur round the tops. Arabella goes on to marry the somewhat hapless, Mr Winkle.

Could this slight connection hint at a similar outcome for Miss Nipper? Hmmm!

Susan’s first description as a womanly-girl with a snub nose, calls to mind the first description of a certain Artful young man:

The boy who addressed this inquiry to the young wayfarer, was about his own age: but one of the queerest looking boys that Oliver had even seen. He was a snub-nosed, flat-browed, common-faced boy enough; and as dirty a juvenile as one would wish to see; but he had about him all the airs and manners of a man.

Oliver Twist – Chapter 8These associations and links enhance and enrich the reading experience and help to render the characters more vital and dynamic large as life.

And hints of Susan will appear in future novels. In her devotion and companionship to her charge/friend, we will meet her again in Clara Peggotty (David Copperfield); Sissy Jupe (Hard Times); Miss Pross (A Tale of Two Cities); Biddy (Great Expectations) and no doubt others (but I haven’t read those ones yet! Yes, I do feel absolutely guilt-ridden about this, but I intend to rectify it)

Susan, we feel, will never desert her mistress. Her devotion, loyalty and service stand in stark contrast the the novel’s theme of pride. In Florence’s darkest and loneliest hours she was there (along with Diogenes) for her mistress! If Florence were in The Fleet prison, Susan, like Sam, would be there too…

A silent look of affection and regard when all other eyes are turned coldly away—the consciousness that we possess the sympathy and affection of one being when all others have deserted us—is a hold, a stay, a comfort, in the deepest affliction, which no wealth could purchase, or power bestow.

The Pickwick Papers – Chapter 21I have a sneaking suspicion that when Susan Nipper grows up, she will be just like Betsey Trotwood (David Copperfield) not just because I can imagine her getting quite Nipperish shouting ‘Janet! Donkeys!’ – though it is easy to imagine Susan doing this.

Mr Toots calls Susan (in rapturous admiration) ‘the most extraordinary woman’

Just as Mr Dick (a future projection of Mr Toots perhaps?) calls Betsey ‘the most extraordinary woman in the world’

A comparison of the two following passages will show that Betsey Trotwood does indeed acquire a little of the Nipper mettle in terms of stairwell sieges waged upon deadly domestic enemies:

To many a single combat with Mrs Pipchin, did Miss Nipper gallantly devote herself, and if ever Mrs Pipchin in all her life had found her match, she had found it now. Miss Nipper threw away the scabbard the first morning she arose in Mrs Pipchin’s house. She asked and gave no quarter. She said it must be war, and war it was; and Mrs Pipchin lived from that time in the midst of surprises, harassings, and defiances, and skirmishing attacks that came bouncing in upon her from the passage, even in unguarded moments of chops, and carried desolation to her very toast.

Chapter 12 – Dombey and SonI thought it my duty to hint at the discomfort my aunt would sustain, from living in a continual state of guerilla warfare with Mrs. Crupp; but she disposed of that objection summarily by declaring that, on the first demonstration of hostilities, she was prepared to astonish Mrs. Crupp for the whole remainder of her natural life.

David Copperfield – Chapter 35There is one character in Dombey and Son whose devotion is equal in every way to that of Susan, and whose mode of expressing it is likewise very similar, and so I will conclude this section with dear Diogenes:

Diogenes already loved her for her own (sake), and didn’t care how much he showed it. So he made himself vastly ridiculous by performing a variety of uncouth bounces in the ante-chamber, and concluded, when poor Florence was at last asleep, and dreaming of the rosy children opposite, by scratching open her bedroom door: rolling up his bed into a pillow: lying down on the boards, at the full length of his tether, with his head towards her: and looking lazily at her, upside down, out of the tops of his eyes, until from winking and winking he fell asleep himself, and dreamed, with gruff barks, of his enemy.

Nipperisms

As Sam Weller has given rise to the Wellerism with his particular eloquence, so Susan Nipper gives us the Nipperism by the same token.

Susan’s mode of speaking – shooting out whatever she had to say in one sentence, and in one breath, if possible – is frequently capitalised upon with her punctuation disappearing in proportion to her excitement rising – the following being the most punctuation free example thereof:

“Oh my own pretty darling sweet Miss Floy!” cried the Nipper, running into Florence’s room, “to think that it should come to this and I should find you here my own dear dove with nobody to wait upon you and no home to call your own but never never will I go away again Miss Floy for though I may not gather moss I’m not a rolling stone nor is my heart a stone or else it wouldn’t bust as it is busting now oh dear oh dear!

What also appears in the above quote is that particular turn of phrase to which Susan often gives vent, and which – because they are largely brilliant – I take the liberty of appending as many examples as I have been able to find of these Nipperisms.

I may be very fond of pennywinkles, Mrs Richards, but it don’t follow that I’m to have ’em for tea.

I may wish, you see, to take a voyage to Chaney, Mrs Richards, but I mayn’t know how to leave the London Docks.

Your Toxes and your Chickses may draw out my two front double teeth, Mrs Richards, but that’s no reason why I need offer ’em the whole set.

though there’s a excellent party-wall between this house and the next, I mayn’t exactly like to go to it, Mrs Richards, notwithstanding!

A person may tell a person to dive off a bridge head foremost into five-and-forty feet of water, Mrs Richards, but a person may be very far from diving.

I may not have my objections to a young man’s keeping company with me, and when he puts the question, may say ‘yes,’ but that’s not saying ‘would you be so kind as like me.

I may not wish to live in crowds, Miss Floy, but still I’m not a oyster.

for though I can bear a great deal, I am not a camel, neither am I if I know myself, a dromedary neither.

I may not be a Amazon, Miss Floy, and wouldn’t so demean myself by such disfigurement, but anyways I’m not a giver up, I hope.

I may not be Meethosalem, but I am not a child in arms.

the more that I was torn to pieces Sir the more I’d say it though I may not be a Fox’s Martyr.

I may not be a Indian widow Sir and I am not and I would not so become but if I once made up my mind to burn myself alive, I’d do it!

I may not be a Peacock; but I have my eyes

for though I’m pretty firm I’m not a marble doorpost, my own dear.

For though I may not gather moss I’m not a rolling stone nor is my heart a stone or else it wouldn’t bust as it is busting now

he may not be a Solomon, nor do I say he is but this I do say a less selfish human creature human nature never knew

In the words of Mr Richard Swiveller, ‘Before I leave the gay and festive scene, and halls of dazzling light, I will with your permission, attempt a slight remark:’

Thank you so much for taking the time to read my post and my outpouring of observations and praise for the wonderful Susan Nipper. Till the next time 😀

-

Charles Dickens’ 1848 Review of William Macready’s King Lear

Published in The Examiner – 27th October 1848

THE THEATRICAL EXAMINER

HAYMARKET THEATRE

MR MACREADY appeared on Wednesday evening in King Lear. The House was crowded in every part before the rising of the curtain, and he was received with deafening enthusiasm. The emotions awakened in the audience by his magnificent performance, and often demonstrated during its progress, did not exhaust their spirits. At the close of the tragedy they rose in a mass to greet him with a burst of applause that made the building ring.

Of the many great impersonations with which Mr Macready is associated, and which he is now, unhappily for dramatic art in England, presenting for the last time, perhaps his Lear is the finest. The deep and subtle consideration he has given to the whole noble play, is visible in all he says and does. From his rash renunciation of the gentle daughter who can only love him and be silent, to his falling dead beside her, unbound from the rack of this tough world, a more affecting, truthful, and awful picture never surely was presented on the stage.

“The greatness of Lear,” writes Charles Lamb, “is not in corporal dimension, but in intellectual: the explosions of his passion are terrible as a volcano: they are storms, turning up and disclosing to the bottom of that sea—his mind, with all its vast riches. It is his mind which is laid bare. This case of flesh and blood seems too insignificant to be thought on; even as he himself neglects it. On the stage we see nothing but corporal infirmities and weakness, the impotence of rage.”

Not so in the performance of Wednesday Night. It was the mind of Lear on which we looked. The heart, soul, and brain of the ruin’d piece of nature, in all the stages of its ruining, were bare before us. What Lamb writes of the character might have been written of this representation of it, and been a faithful description.

To say of such a performance that this or that point is most observable in it for its excellence, is hardly to do justice to a piece of art so complete and beautiful. The tenderness , the rage, the madness, the remorse, and sorrow, all come of one another, and are linked together in one chain. Only of such tenderness could come such rage; of both combined, such madness; of such a strife of passions and affections, the pathetic cry

Do not laugh at me; For, as I am a man, I think this lady To be my child Cordelia; of such a recognition and its sequel, such a broken heart. Some years have elapsed since we first noticed Miss Horton’s acting of the Fool, restored to the play as one of its most affecting and necessary features, under Mr Macready’s management at Covent Garden. It has lost nothing in the interval. It would be difficult indeed to praise so exquisite and delicate assumption too highly. Miss Reynolds appeared as Cordelia for the first time, and was not (except in her appearance) very effective. Mr Stuart played Kent, and, but for fully justifying his banishment by his very uproarious demeanour toward his sovereign, played it well. Mr Wallack was a highly meritorious Edgar. We have never seen the part so well played. His manner of delivering the description of Dover cliff—watching his blind father the while, and not looking as if he really saw the scene he describes, as it is the manner of most Edgars to do—was particularly sensible and good. Mr Howe played with great spirit, and Mrs Warner was most wickedly beautiful in Goneril. The play was carefully and well presented, and its effect upon the audience hardly to be conceived from this brief description.

-

Allusions to Shakespeare in Dickens’ Dombey and Son

Two writers that it is abundantly clear that I admire and, quite frankly, can’t get enough of, are William Shakespeare and Charles Dickens. Both masters of their craft, excelling in wordsmithery and invention of the highest order, and I doubt whether any comments or observations of mine will do much to swell the reputations of these giants of English Literature. But still, one feels one must stand up and be counted, and throw one’s hat into the ring, as it were. So there it is… I’ve said it 😊

Reading Dombey and Son, I have found particular delight in the occasions when Dickens makes allusion to the works or words of Shakespeare. Enough delight to send me off searching the web to see if I could find a list. My search was fruitless, and so I thought I’d jot them down – mainly for my own reference, I suppose – but there may be more like me out there who would be grateful to stumble upon such a list as here follows.

I feel that there were a few more than I have listed here, but it’s a long novel and I didn’t have the idea to jot them down until after I’d finished it.

I have listed the quotes by Chapter and included after each the lines from Shakespeare to which they allude. One of them requires a whole section from the scene, but otherwise they are just a few lines from the source.

I’d be happy to receive word of any more that are found by observant readers of the novel, so if you do, please let me know in the comments.

Chapter 5:

Miss Tox was so transported beyond the ignorant present as to be unable to refrain from crying out, “Is he not beautiful Mr Dombey!”

LADY MACBETH:

Thy letters have transported me beyond

This ignorant present, and I feel now

The future in the instant.

Macbeth – Act 1 Scene 5Little Paul might have asked with Hamlet “into my grave?” so chill and earthy was the place.

POLONIUS [aside] Though this be madness, yet there is a method in’t.-

Will You walk out of the air, my lord?

HAMLET

Into my grave?

Hamlet – Act 2 Scene 2Chapter 7:

…and where the most domestic and confidential garments of coachmen and their wives and families, usually hung, like Macbeth’s banners, on the outward walls.

MACBETH:

Hang out our banners on the outward walls;

Macbeth – Act 5 Scene 5

The cry is still ‘They come:’Chapter 8:

…and on these occasions Mr Dombey seemed to grow, like Falstaff’s assailants, and instead of being one man in buckram, to become a dozen.

(this one is best demonstrated by the whole section from the scene in Henry IV Part I)

FALSTAFF. Nay, that’s past praying for: I have peppered two of them; two I am sure I have paid, two rogues in buckram suits. I tell thee what, Hal, if I tell thee a lie, spit in my face, call me horse. Thou knowest my old ward; here I lay and thus I bore my point. Four rogues in buckram let drive at me—

PRINCE HAL. What, four? thou saidst but two even now.

FALSTAFF. Four, Hal; I told thee four.

POINS. Ay, ay, he said four.

FALSTAFF. These four came all a-front, and mainly thrust at me. I made me no more ado but took all their seven points in my target, thus.

PRINCE HAL. Seven? why, there were but four even now.

FALSTAFF. In buckram?

POINS. Ay, four, in buckram suits.

FALSTAFF. Seven, by these hilts, or I am a villain else.

PRINCE HAL. Prithee, let him alone; we shall have more anon.

FALSTAFF. Dost thou hear me, Hal?

PRINCE HAL. Ay, and mark thee too, Jack.

FALSTAFF. Do so, for it is worth the listening to. These nine in buckram that I told thee of—

PRINCE HAL. So, two more already.

FALSTAFF. Their points being broken,—

POINS. Down fell their hose.

FALSTAFF. Began to give me ground: but I followed me close, came in foot and hand; and with a thought seven of the eleven I paid.

PRINCE HAL. O monstrous! eleven buckram men grown out of two!

FALSTAFF. But, as the devil would have it, three misbegotten knaves in Kendal green came at my back and let drive at me; for it was so dark, Hal, that thou couldst not see thy hand.

PRINCE HAL. These lies are like their father that begets them; gross as a mountain, open, palpable. Why, thou clay-brained guts, thou knotty-pated fool, thou whoreson, obscene, grease tallow-catch,—

FALSTAFF. What, art thou mad? art thou mad? is not the truth the truth?

Henry IV Part 1 – Act 2 Scene 4Chapter 18:

But though Diogenes was as ridiculous a dog as one would meet with on a summer’s day;

(this one is perhaps a little tenuous a link, but it very much reminded me when I read it of Peter Quince trying to convince Nick Bottom that Pyramus is the part for him)

PETER QUINCE. You can play no part but Pyramus; for Pyramus is a sweet-faced man; a proper man, as one shall see in a summer’s day; a most lovely gentleman-like man: therefore you must needs play Pyramus.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream – Act 1 Scene 2Chapter 21:

Mr Dombey and the Major found Mrs Skewton arranged, as Cleopatra, among the cushions of a sofa: very airily dressed; and certainly not resembling Shakespeare’s Cleopatra, whom age could not wither.

ENOBARBUS:

Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale

Antony and Cleopatra – Act 2 Scene 2

Her infinite variety:Chapter 22:

Mr Carker the Manager, sly of manner, sharp of tooth, soft of foot, watchful of eye, oily of tongue, cruel of heart, nice of habit, sat with a dainty steadfastness and patience at his work, as if he were waiting at a mouse’s hole.

(This is a tricky one as it neither references nor alludes to anything specifically Shakespearian. I have included it however as the underlined section bears a more than passing similarity to the following – Spoken by Edgar while he is disguised as Poor Tom)

EDGAR

False of heart, light of ear, bloody of hand; hog in sloth, fox

in stealth, wolf in greediness, dog in madness, lion in prey.

King Lear – Act 3 Scene 4Chapter 23:

…but that he, Mr Carker, was the be-all and the end-all of this business

(this idiom was actually coined by Shakespeare in the same speech which saw the first appearance of the word ‘assassination’ in print)

MACBETH:

that but this blow

Might be the be-all and the end-all here

Macbeth – Act 1 Scene 7Chapter 27:

Munching like that sailor’s wife of yore, who had chestnuts in her lap, and scowling like the witch who asked for some in vain

FIRST WITCH:

A sailor’s wife had chestnuts in her lap,

Macbeth – Act 1 Scene 4

And munch’d, and munch’d, and munch’d:—

‘Give me,’ quoth I:

‘Aroint thee, witch!’ the rump-fed ronyon cries.Chapter 29:

Mrs Chick drew off as from a criminal, and reversing the precedent of the murdered king of Denmark, regarded her more in anger than in sorrow.

HAMLET. What, look’d he frowningly.

HORATIO. A countenance more in sorrow than in anger.

Hamlet – Act 1 Scene 2Chapter 38:

This was intended for Mr Toodle’s private edification, but Rob the Grinder, whose withers were not unwrung, caught the words as they were spoken.

Your Majesty, and we that have free souls, it touches us not. Let the gall’d jade wince; our withers are unwrung.

Hamlet – Act 3 Scene 2Chapter 54:

When Edith says (In this quite extraordinary chapter) “I have something lying here that is no love trinket, and sooner than endure your touch once more, I would use it on you—and you know it, while I speak—with less reluctance than I would on any other creeping thing that lives,” the line, no less than the scene itself, has echoes of the confrontation between Richard and Lady Anne in Richard III.

This is another of those tenuous links which I may be seeing and which was not necessarily intended 🙂

More direful hap betide that hated wretch,

Richard III – Act 1 Scene 2

That makes us wretched by the death of thee,

Than I can wish to adders, spiders, toads,

Or any creeping venom’d thing that lives!Chapter 57:

The amens of the dusty clerk appear, like Macbeth’s, to stick in his throat a little

MACBETH:

But wherefore could not I pronounce ‘Amen’?

Macbeth – Act 2 Scene 2

I had most need of blessing, and ‘Amen’

Stuck in my throat.Chapter 58:

Mrs Wickam then sprinkled a little cooling-stuff about the room, with the air of a female grave-digger, who was strewing ashes on ashes, dust on dust—for she was a serious character—and withdrew to partake of certain funeral baked meats downstairs.